I wrote this for a publication, but unfortunately, they published a review of a different Gary Indiana book at the same time, so it did not fit at that moment. Instead of just holding on to it, I am sharing it differently.

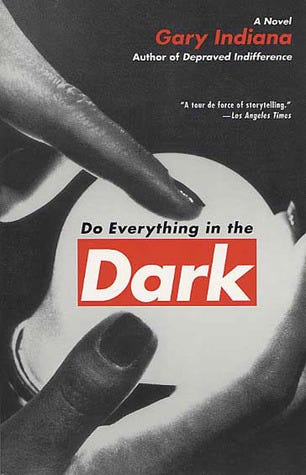

Do Everything in the Dark

Gary Indiana

Semiotext(E), pp. 296, $16.95

Originally published in 2003, Do Everything in the Dark was republished in 2023 by Semiotext(E). Do Everything in the Dark is Gary Indiana’s way of coping with all the changes that New York experienced during the 1980s. It is fitting that it got republished — with Covid over, there is a little bit of space to reflect on how New York City has changed.

Do Everything in the Dark, through the fictionalized eyes of Gary Indiana’s friends from downtown New York during the summer before 9/11, is a reflection on the arcs of their lives, while also a lamentation for how much New York has changed. The novelization of actual events is an old tool for Gary Indiana. He used it before in his true-crime trilogy, and it defamiliarizes events and people that may have been too familiar to develop a new perspective on. The fictionalized Indiana narrates the fate of his various friends, as they slowly, but surely, return to New York after their years in internal or external exile from the city. Time, for the most part, had not improved their situations, or had made them even worse.

Perhaps as a way to equalize the fates his friends had, he characterized his friends depending how well, or not well off they ended. Indiana's casting of the downtown writer Cookie Mueller was kind. Susan Sontag, as Tova Finkelstein, is portrayed as an intellectual menace who attempts at every moment to gather attention for herself. Even at funerals. Through all his characters, he is trying to prove that trying to change a situation does not necessarily mean that situation will be resolved. Sometimes efforts to change make one worse.

The majority of the novel does not take place in New York, with only the narrator and a few other characters remaining in, or even near, the city, until the very end. Initially, they are all scattered across the world. One fled to the Mediterranean to drink and cavort with rent boys. A couple moved to New Mexico in-theory for a few months, which dragged far longer than expected. Even for one character that moved only to upstate New York, New York City proper feels a world away.

For the few characters in New York, the city feels both cramped and empty at the same time. Not necessarily crammed with people, but crammed with the mindspace people had in the minds of others. At the same time, Indiana makes it seem that life only happens not just in New York, but only in downtown New York.

Indiana accentuates this when narrating sections contained in New York. Most blatantly, one resident states: “Life is only occurring at restaurant X, bar Y, and night club Z.” He also notes that the characters that remain in New York do not think about those who left very much, or even know that they left. Empty apartments and art are what remain, if anything, of the people who fled New York for supposedly better climes. One of the characters, Malcolm, puts this concisely: “People came here and made their mark, and then they could leave for years without anyone suspecting they were gone.” Indiana even manages to make one character's temporary residence in the Bronx into a permanent mental exile from New York City.

There are benefits and downsides to the diversity of characters. On one hand, Indiana ensures that each arc isn’t completely isolated. Through his characters' letters and discussions, the distant friends are in communication with one another. On the other hand, this does lead to a choppy narrative, where some characters get more coverage than others. This may also be tied to how Indiana classified each character based on their social status, which can sometimes read as fairly arbitrary and all over the place. Even so, the changes in perspective make for morbidly enjoyable reading.

Do Everything in the Dark is a New York novel, despite most of the characters being absent from the city.. The New York novel is, that the novel not only takes place in New York, but the fact that it is set in New York is a key part of the story. Books like Visit from the Goon Squad, City on Fire, or The Flamethrowers represent nostalgic pictures of New York in the 1960s and 1970s. There are depictions of New York in the 1980s such as Bright Lights, Big City, or American Psycho that represent darker pictures of New York, with success for some, suffering for others, and even downward spirals into psychopathy.

What separates Do Everything in the Dark from all these accounts of New York is a few things. First, Do Everything in the Dark is far more focused on “downtown” New York, and specifically his friend group, versus the entire city. Second, despite being about New York, it is the absence of New York that dominates the narrative. While some of Indiana’s friends are living in New York and reminiscing about the scene, they are in the minority.

There is also Indiana’s willingness to inflict tragedies on his main characters. While the characters of the aforementioned novels do go through struggles, they are in the end provided closure — something Gary Indiana does not provide for all his friends. One friend spirals into drug addiction and loses her mind after she electrocutes herself. Another remains in a muddled marriage in downtown New York. Indiana takes the realistic, if depressing, view that changes in situations don’t necessarily mean improvements in said situations. Just because you left New York doesn’t mean that will solve the problems that you had.

That change does not always lead to improvement is perhaps a more honest portrayal of life than what typically happens in these novels. Privileges do make a significant difference in whether people survive or break in the face of adversity. The friend who electrocuted herself remains alive until the very end, due to having family money to pay for her treatment. Even then, she becomes a shadow of her former self.

But what Do Everything in the Dark shares with many New York novels is that it is a lamentation. Specifically, a lamentation of downtown New York City of the 1980s, partly because this was a depressing period for Gary Indiana even as it was one of professional success. Indiana, a writer and cultural gadfly, achieved a new level of notoriety in the art world due to his role as a art critic at the Village Voice from 1985 to 1988.

This period, however, coincided with the AIDS crisis, with many of his friends such as Cookie Mueller succumbing to the disease. With all your friends dying despite achieving some respectability, lamentation is understandable. The world becomes recognisable without your friends, especially if you can’t enjoy success with them. In a recent interview with New York Times Style Magazine, Indiana said the East Village has “completely changed.” The world of 1980s New York to him is completely gone.

One can only look at how New York has changed. With average rent in Manhattan nearly $5,000, how can a cultural scene exist if the average person can’t sustainably live there? The cultural environment for literary and cultural criticism has also gotten worse. One can point to the decline of the book review section in newspapers, or that critics have become nicer due to economic precarity. Examples focused on downtown New York include the death of the Village Voice, or the near death of Bookforum. With concerns like this, it is understandable to think that the world of the past is gone, and that cultural criticism is on a terminal downswing.

I would disagree with this point. There are some people that still appreciate the work that is cutting cultural criticism. The only reason I heard of Do Everything in the Dark is that I stumbled across a review of Gary Indiana’s work in the New Left Review. Out of curiosity, I decided to start to read Gary Indiana, starting with Resentment.I then discovered through reading more reviews of his books, and noticing the introductions, that some people have enough appreciation to review and blurb his books, such as Christian Lorentzen or Tobi Hasslet, who possess a similar kind of skill in criticism.

As long as some people have those connections, either personally or through literature, the past is not completely gone. It is possible, at least in literature, to revisit the past and deliver its best traits to the present. And in truth, there will always be people trying to make it as writers in New York doing critical cultural writing, from Brooklyn socialists to alt-lit Manhattan technologists. Even Bookforum, thought left for dead after the Artforum deal, was resurrected this year. So perhaps the idea of a downtown New York of writers trying to figure things out is not dead yet.

Do Everything in the Dark is an enjoyable, if grim, nostalgic novel about nostalgia for 1980s New York. Unlike some approaches to the New York novel, it takes the pessimistic view of how life plays out. It is perfect that Gary Indiana closes off the book just before 9/11. The history of downtown New York can remain unsullied by history.